ARTICLE AD BOX

Bethany Elliott is a freelance journalist published in outlets like Unherd, the Critic, the Fence and the Daily Mash. He’s a regular contributor on BBC radio and television.

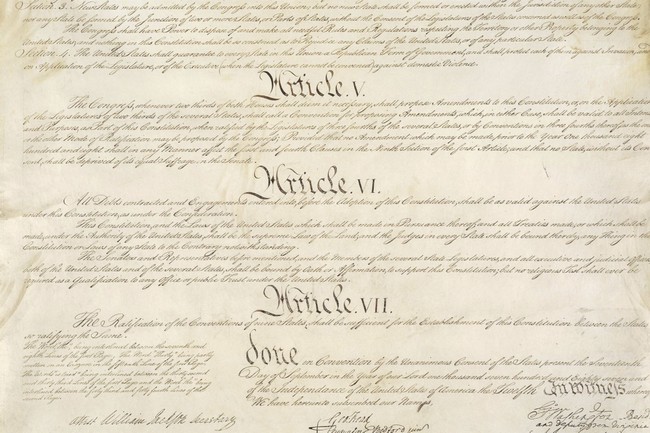

After more than a decade in government, the U.K.’s unpopular Conservative Party is languishing in the polls. The Tories are grabbing headlines more through scandal and mishap than any policy announcement, and in the forthcoming election, even the seats of some ministers look to be imperiled. Meanwhile, waiting in the wings is a centrist Labour leader eager for a landslide win.

That was the case in 1997 — and it’s also the case today

Certainly, current polling suggests that July’s election will redraw the electoral map in the style of 1997. As it stands, 77 Conservative MPs will be stepping down at the next race, exceeding the 72 Tories who didn’t contest their seats in 1997. Meanwhile, a January survey by YouGov predicted the Conservatives will hold on to just 169 seats against Labour’s 385.

No wonder Conservative peer David Frost recently concluded the Tories face “a 1997-style wipeout — if we are lucky.”

So, is history truly repeating itself? And, if we’re in for a rehash of the last Labour landslide, what lessons do the Conservatives of that generation have for today’s Tory MPs as they — to quote former Secretary of State for Defence Ben Wallace — “march towards the sound of the guns”?

One warning for Prime Minister Rishi Sunak to heed would be that it isn’t “the economy, stupid.” Sunak has reportedly called the election hoping voters will reward him for falling inflation and the promise of better economic times. But counting on the economy didn’t work for the Tories in 1997 — even though it really was improving.

“There was a general view that the economy was actually in very good shape,” recalled former Chief Secretary to the Treasury Jonathan Aitken. “We’d got everything going in as good a direction as it could be, but I just sensed a much more deep-seated distaste, distrust, exhaustion, dislike of the Tories.”

“Even if you’re doing the right thing and things are going well economically,” said former Foreign Secretary Malcolm Rifkind, “the public quite often get bored. They want a change and that’s entirely reasonable.”

Indeed, by the time the 1997 election rolled around, following a preelection budget and interest rate cuts, the Tories had achieved an eight-year high in quarterly growth, which merely served as a nice housewarming gift for incoming Labour Chancellor Gordon Brown.

Additionally, today’s situation may actually be worse than even the party itself realizes. “There was pessimism [in 1997] but not deep pessimism,” Aitken said. “I was one of the few who really thought there could be a [Tony] Blair landslide — that was very much a minority view among Conservatives. Most of us thought he would win but maybe with a majority of 50, conceivably 80.” When Aitken voiced fears in the run-up to the election that he may lose his seat, his colleagues at the House of Commons reassured him that only those with majorities below 10,000 should worry.

“We knew it was extremely likely” that Labour would win, concurred Rifkind, but “we didn’t expect the scale of it” — something Conservative candidates may wish to bear in mind when they hear Sunak claim that May’s local election results indicate a hung parliament.

So, how exactly does an incumbent lawmaker maintain motivation when they know — and, perhaps more importantly, their constituents know — that their name will soon be losing those two most important letters, “M” and “P”?

After more than a decade in government, the U.K.’s unpopular Conservative Party is languishing in the polls. | Dan Kitwood/Getty Images

After more than a decade in government, the U.K.’s unpopular Conservative Party is languishing in the polls. | Dan Kitwood/Getty Images While some Tories have reportedly refused to go out electioneering in the days since the starter pistol was fired, Rifkind’s tip is to simply enjoy door-to-door campaigning. “In 1997, it was a complete waste of breath in my personal view,” Rifkind said. “I deliberately enjoyed getting into conversations because it was just more stimulating, not because I expected to convert the person at the door.”

Later, in 2005, Rifkind maintained his commitment to making campaigning fun by canvassing at the home of former Labour Cabinet Minister Tony Benn. Phoning through the intercom, Rifkind wangled an invitation for tea, only for the Labour grandee to correctly suspect he secretly had a “whole bloody troupe” of journalists in tow.

“Enjoy the human side of electioneering,” Aitken similarly urged. “There’s always humor, there’s always humanity, there’s always stories, there’s always a chance to enjoy a pint. And don’t show your own pessimism to your supporters.” When the moment comes, “losing well and graciously is important,” he said.

“Politics is purely, completely unpredictable, and you’ve got to have a personality that can cope,” Rifkind added.

And for those who do survive the carnage, there’s the prospect of remaining in opposition interminably. Former Attorney General Dominic Grieve was one of only 32 new Tory MPs elected in 1997; “it was weird,” he recalled. “We arrived in the Commons having been elected despite the catastrophe that had overtaken the party, quite bright-eyed and bushy-tailed, eager to get on with things, to find all our colleagues who had been there previously suffering from PTSD. They were wandering around the Commons looking completely smashed to pieces.”

“The whips’ office location changes, everything changes. On top of that, they were looking around on their own benches, and 150-plus of their colleagues had disappeared. That was very traumatic, and it took them months to recover. As an opposition, we were completely useless for the first six months,” he said.

Still, while today may offer parallels with the last time Tory whips needed to pack up their offices, there are also key differences.

To the Conservatives’ advantage, current Labour leader Keir Starmer isn’t former Labour Prime Minister Tony Blair. “One shouldn’t underestimate the impact Blair’s personality had,” said Rifkind. “A leader who not only was seen as competent but positively charismatic and exciting.” Even die-hard Conservatives in Rifkind’s constituency admitted being “really impressed” by Blair, saying “he looks like just the sort of leader that Britain needs at the moment.”

In comparison, Starmer appears a poor facsimile. “Starmer is not charismatic; I don’t think even Keir Starmer would claim to be Tony Blair in terms of personal charisma,” Rifkind said.

However, to the party’s disadvantage, Sunak isn’t Blair’s predecessor, former Tory Prime Minister John Major, either. Drawing comparisons with the greater political status Major commanded in 1997, Rifkind noted that Major’s “personal position and stature were much more substantial than Rishi Sunak’s at the moment — through no fault of Rishi Sunak’s.” Having been prime minister since 1990, and having won 1992’s general election, Major “had the authority and legitimacy that goes with that,” he said.

Finally, the public mood may be even more hostile now. “The scandals in my years were minor in comparison with today. We were hated by some. Today, worse — despised,” concluded former Conservative MP Olga Maitland. So much so that a repeat of 1997’s landslide defeat and 13 years in opposition may, in fact, be too hopeful a prospect for today’s Tories.

Perhaps, of all the lessons from 1997, the most important words for today’s despairing Tories to remember are these: Things can only get better.

.png)

9 months ago

5

9 months ago

5

English (US)

English (US)