ARTICLE AD BOX

“We don’t need magazine profiles,” California Governor Gavin Newsom told me. “We don’t need any problems.”

We were sitting on opposing couches in his Sacramento office, a makeshift space across the street from his usual suite in the state capitol, currently being renovated. Newsom, leaning his head back into his intertwined hands, looked every bit the sleek pol he plays on TV—the big smile, the suit, the hair gel. He had just led me on a tour of this sterile habitat that he likens to a “dentist’s office.” Everything about it felt slapdash and temporary. “People know they’re not here for very long,” said Newsom, who is 56 but emits the frenetic energy of an upstart.

This aura can invite distrust. So can participating in magazine profiles when you don’t want to be seen as buffing your national image at the expense of being a team player—the team being President Joe Biden’s reelection campaign.

“The shadow campaign” is what Newsom calls the theory, happily promoted by Republicans and the occasional Democrat, that he’s been plotting a clandestine effort to supplant Biden as his party’s nominee. Newsom is clearly sensitive to this perception and eager to disprove it. He has spent the past several months vouching for the president in a variety of adverse settings: after a Republican debate at the Reagan Library, on Fox News, and across several red states, from South Carolina to Idaho. He managed to put off our interview for nearly two months, long enough for Biden to clinch his nomination. By the time we met at the end of March, Newsom had fashioned himself as a kind of presidential super-surrogate—a chief alleviator of fears about Biden’s lagging poll numbers, advanced age, and ability to again defeat Donald Trump.

But being a super-surrogate requires a performative humility, subordinating one’s own ambition to the candidate’s. This is not something that comes naturally to a restless dazzler such as Newsom. “You’re good at this,” Bill Maher told the governor during a January appearance on HBO’s Real Time, praising Newsom’s pugnacious strikes against Republicans and his willingness to be “kinda mean” at times. Newsom then blasted off into a diatribe about how Democrats need to stop being so timid, earning an extended ovation. At which point, Maher paused, looked approvingly at Newsom, and asked: “Can you teach that speech to Biden?”

[Ronald Brownstein: The Democrats’ new spokesman in the culture wars]

Newsom chuckled awkwardly. He did the same when I recounted the Maher exchange to him. The subtext is obvious, and gets at the thorniness of being Newsom these days: the risk of being so “good at this” that it can seem like he’s running himself.

When pressed about his own presidential aspirations, as he still often is, Newsom is adept at pivoting to his reverential spiel about Biden. “He’s doing things that I could never imagine doing,” the governor told me. He said he has gotten to know Biden and has “really grown to deeply admire him, with conviction.” Newsom has objected in numerous ways, in numerous forums, to the idea that the 81-year-old president is slowing down. “You become an SNL meme,” he said of the challenge Biden surrogates face when trying to defend the president’s geriatric fitness in fresh and credible ways.

I mentioned to Newsom that age seems to be the intractable issue for Biden: Large majorities of Americans keep telling pollsters, over and over, that he is too old to run again. At a certain point, can anything really be done? Newsom swerved the conversation onto delicate terrain.

“Well, there’s Pretagen, and all those things on TV that seem to argue—to help—with that,” he said. He seemed to be referring to an over-the-counter supplement called Prevagen that supposedly promotes brain health. “I can’t turn on the damn TV without the vegetable and fruit supplements,” said Newsom, who professes to watch a lot of Fox News.

“Have you talked to Biden about maybe going on a more vigorous Prevagen regimen?” I deadpanned.

“Look, I mean, I was—” Newsom faltered for a moment. “I don’t know if I was joking, but I was lamenting about how many different ways, on different networks, I’ve answered this question in an effort to try to answer a little differently each time.”

On that, Newsom succeeded. His Prevagen answer was novel, if risky. Sometimes he can’t help himself.

President Joe Biden speaks with California Governor Gavin Newsom as Biden arrives in Santa Clara County, California, in June 2023. (Doug Mills / The New York Times / Redux)

President Joe Biden speaks with California Governor Gavin Newsom as Biden arrives in Santa Clara County, California, in June 2023. (Doug Mills / The New York Times / Redux)

Newsom has solicitous eyes that often dart around a room, as if he’s scanning for something that might entertain his guest, or him. He is a fourth-generation Californian who himself embodies many dimensions of the unruly dream-state he is attempting to govern: He is profuse and thirsty at the same time, high-reaching, a bit dramatic, and never far from some disaster.

“I don’t want to be derivative,” Newsom said in our interview. He loves the word derivative almost as much as, he says, he hates things that are derivative—the kind of repetitive sound-biting that can be as basic to a politician’s job as throwing a baseball is to being a pitcher (which Newsom was in his youth, a lefty).

I have known Newsom for about 15 years, but hadn’t officially interviewed him since he was finishing his second term as mayor of San Francisco and preparing to run for governor in 2010. The campaign was short-lived, as it became clear that Newsom had limited reach beyond the Bay Area and little shot against California’s former and future governor, Jerry Brown. Newsom instead ran for lieutenant governor, winning the privilege of spending eight restive years as Brown’s understudy.

[From the June 2013 issue: Jerry Brown’s political reboot]

One of the few highlights of Newsom’s tenure, he told me, occurred in 2013, when Brown was on a trade mission to China. Newsom, in his brief stint as acting governor, issued a proclamation designating the avocado as California’s state fruit. Newsom said he felt like Brown was not showing him or his office “a lot of respect,” so he undertook the avocado gambit as a benign “act of defiance.” (He insists that his love of avocados is genuine and that he tries to eat one “six to seven days a week.”) The rogue operation extended to artichokes (which Newsom named as the state vegetable), rice (the state grain), and almonds (the state nut).

Newsom seemed to take immense pride in this small harvest of edicts, milking them for laughs and press coverage. He boasted of the “cornucopia of landmark accomplishments” that he had achieved “over these magical six days.” More than a decade later, Newsom still sounds amused, even if Governor Brown, upon his return from China, apparently was not. “I don’t know that amused and Jerry Brown have ever been used in the same sentence,” Newsom said. (Brown declined to be interviewed, but praised Newsom in a brief statement for providing “much needed continuity” on climate and China policy—two issues central to Brown’s time in office.)

For much of his political career, Newsom has been perceived as something of a wild child. He has nurtured that image by getting into occasional trouble. In 2007, as mayor, he admitted to an affair with his appointments secretary, who’d been married to Newsom’s close friend and deputy chief of staff; this was following the breakup of Newsom’s first marriage—to the future Fox News personality Kimberly Guilfoyle, who is now engaged to Donald Trump Jr. As recently as 2020, Newsom violated COVID restrictions by attending a group dinner at the French Laundry, one of California’s fanciest restaurants, which became a major issue in an unsuccessful campaign to recall him.

His breakneck impulses also resulted in the signature policy action that would establish Newsom as a national figure—his 2004 order for San Francisco to grant marriage licenses to same-sex couples. “It’s the Roger Bannister theory of life,” Newsom told me, referring to the English runner who broke the four-minute-mile barrier. Newsom said that, like Bannister, he was young and dumb and “didn’t know that he couldn’t.” He quoted his political idol, Robert F. Kennedy Sr., who in a 1966 address in South Africa said that the world “demands the qualities of youth; not a time of life but a state of mind, a temper of the will, a quality of imagination, a predominance of courage over timidity.”

Today, Newsom has logged two terms each as a big-city mayor and as lieutenant governor, plus five years leading the nation-state of California. He married again in 2008, and has four children with his wife, Jennifer Siebel Newsom, a filmmaker and former actor. Newsom’s tenure as governor has featured high-profile moves that have positioned him as a national avatar of blue-state boosterism: an executive order mandating that new cars sold in California be zero-emission by 2035; a call for a constitutional amendment that would raise the legal age to purchase firearms to 21; a commitment to make California a “sanctuary” for abortion access.

As much as Newsom believes that it’s important to “continue to iterate,” I was struck by how often he talked about keeping experienced mentors close by. During the early crisis months of COVID, Newsom told me, he convened Zoom meetings with his living predecessors—Brown, Arnold Schwarzenegger, Gray Davis, and Pete Wilson. “To have these kinds of legendary figures—” Newsom said, shaking his head. Sometimes he would just sit back and absorb the exchanges. “Just the weird history, and the dynamic—it was a lot of fun,” Newsom said. He referred to the group as his “council of the elders.”

[From the April 2023 issue: Arnold Schwarzenegger’s last act]

“He has grown, learned, and matured in terms of his approach,” says Representative Nancy Pelosi, the former speaker of the House, who has known Newsom since “before he was born.” (Bill Newsom, Gavin’s father, was a well-connected Bay Area judge—appointed to the bench by Jerry Brown—whose sister was married to the brother of Pelosi’s husband, Paul.)

Pelosi is among a gallery of California political giants who have nurtured Newsom through his career. Willie Brown, the longtime speaker of the state assembly and mayor of San Francisco, appointed Newsom to his first political job in 1996, on the city’s Parking and Traffic Commission, and later to a vacant seat on its board of supervisors. Newsom told me he also took boundless knowledge from watching Jerry Brown for eight years in Sacramento, even though the two almost never interacted and Newsom’s impact as lieutenant governor was mostly limited to his heroic advocacy of the avocado.

By any measure, Brown had a remarkable leadership résumé—two previous terms as governor in the 1970s and ’80s, three presidential campaigns, stints as California’s attorney general and secretary of state, time as chair of the state Democratic Party, and two terms as mayor of Oakland. Like Newsom, he was known early in his career for his zesty and impatient style. “He was a man on a mission. He was the guy running for president over and over again,” Newsom said of Brown. But the late-career version of Brown “was just a different Jerry,” Newsom said. He sometimes watched Brown and wondered, “Why hasn’t he said anything about issue x, y, z?” And then, a few months later, the shrewdness of Brown’s silence would reveal itself.

“I want temperance. I want wisdom. I want someone who can govern, someone that’s not unhinged,” Newsom told me. He was talking now about Joe Biden, and trying to make the case that the president’s age should be seen as an asset, just as it was for Brown near the end of his career. It’s a compelling parallel, except that Brown left office at 80, and Biden is running for his second term at a year older. I noted to Newsom that Biden clearly has been well served by his wealth of experience, but that what his skeptics question is his ability to beat Donald Trump. “It’s an election question, I got it,” Newsom told me. “You gotta win.”

As the president departed on a trip to Los Angeles in February, a reporter shouted a question from the White House lawn about whether Newsom should be standing by in case a Democratic alternative was needed for 2024. Biden blew it off, but the episode highlighted the ongoing nuisance of the age issue, which had just been revived by Special Counsel Robert Hur’s report describing the president as “a sympathetic, well-meaning, elderly man with a poor memory.” As Newsom has denied any interest in replacing Biden, the president in turn has flattered him on the subject. “He’s been one hell of a governor, man,” Biden said of Newsom during a stop in San Francisco last November. “He could have the job I’m looking for.”

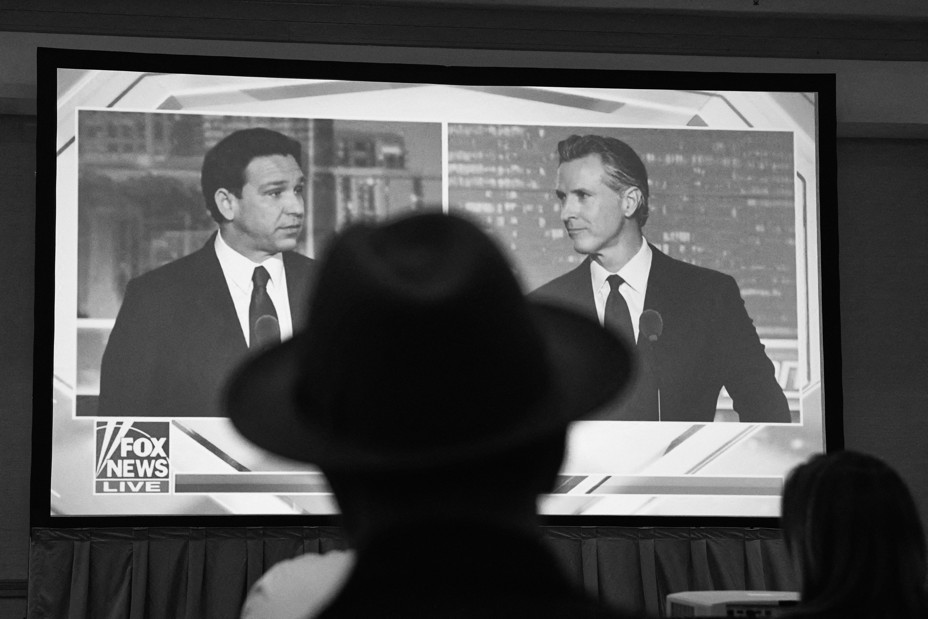

For much of last year, however, aides close to the president were wary of Newsom’s motives. He aroused particular suspicion by challenging Florida Governor Ron DeSantis to debate him on Fox News in November, in what the network billed as the “Great Red vs. Blue State Debate,” to be “moderated” by Sean Hannity. Newsom told me he would’ve skipped the debate if asked, but he heard nothing from the White House. “They never said, ‘Don’t do it, don’t do it,’” he said. “But I can imagine they were like, What is he doing?” (A spokesperson for Biden’s campaign did not respond to a request for comment.)

Viewers watch Florida Governor Ron DeSantis debate California Governor Gavin Newsom in Alpharetta, Georgia, in November. (Elijah Nouvelage / Reuters)

Viewers watch Florida Governor Ron DeSantis debate California Governor Gavin Newsom in Alpharetta, Georgia, in November. (Elijah Nouvelage / Reuters)

“Yes, there was chatter,” Jeffrey Katzenberg, the DreamWorks co-founder, who’s a longtime supporter of Newsom and a co-chair of the Biden reelection campaign, confirmed to me. “It wasn’t, ‘This is terrible. He shouldn’t be doing it.’ But I do think there was chatter like, ‘Really?’” Katzenberg added. “‘Why give DeSantis the platform? You’re elevating him.’”

Senator Laphonza Butler of California, whom Newsom appointed to her job in October after the death of Senator Dianne Feinstein, told me: “Had I been advising him, I’m not sure I would have said, ‘Yeah, that’s a great idea.’”

Newsom went ahead with the debate anyway, in part, he said, because he had already committed to it. “I’m glad for no other reason [than] you develop a muscle you didn’t know you had,” he told me. It was helpful, he said, that the event was delayed for months, allowing Newsom to prove himself a reliable partner to the White House. He has brought in large sums of cash for the reelection campaign and, last March, started a PAC that has raised more than $9 million for Biden and other Democratic candidates. Still, the Fox spectacle, which occurred not long before the start of the primaries, was an odd look for both participants.

[David Frum: Ron DeSantis debates his grievances]

Newsom received generally positive reviews. “I thought he made some solid points,” Butler said. “He made DeSantis stumble.” He delivered perhaps the line of the night when he mentioned that he and DeSantis had something in common: “Neither of us will be the nominee for our party in 2024”—another signal to the White House that Newsom was fully onboard. It was also one of several times that Newsom hammered DeSantis over how Trump was beating him badly in the Republican primary, something that undoubtedly delighted the former president.

Trump represents a more natural foil to Newsom than DeSantis. Both are outsize, sensitive, and at times self-immolating showmen. Newsom clearly enjoys pitting himself against the former president, whose deep unpopularity among Democrats makes his antagonism an unquestioned political asset. Trump recently started calling the governor “New-scum,” which Newsom belittled to me as a lame “seventh-grade nickname.”

At the start of our interview, Newsom pointed across his room to a photo of himself with Donald and Melania in the Oval Office. “My staff put it up there, kind of as a joke, and I kept it,” Newsom told me. It is also a conversation piece, over which Newsom became quite animated. He appears to have a fascination with Trump, and not just as an evil adversary. Newsom, who campaigned in 2018 on a pledge to make California “a resistance state,” likes to mention that he worked well with Trump during his first two years in Sacramento. “We had the baseline of a relationship that benefited California significantly,” he told me. He watched Trump closely and tried to decipher how best to manage the needy president during COVID and severe wildfires in his state. He stroked Trump in public. “I want to thank you and acknowledge the work that you’ve done to be immediate in terms of your response,” Newsom told Trump in front of reporters at Sacramento’s McClellan Airport during a visit from the president in September 2020.

As Newsom continued a prolonged riff about Trump during our interview—what he learned watching Trump’s “dialectic” with the media or riding with him on Air Force One—he sounded strangely captivated, as if he had been privileged to observe a feral and predatory peacock in the wild. The association sounded more important to Newsom than I might have imagined.

Newsom told me that every time he placed a call to Trump in the White House, someone would patch him through or the president would call right back. That changed when Newsom reached out a few days after Trump lost the 2020 election. He heard nothing. “And I was like, Wow,” Newsom said. “And then I called a few days later—I figured he was busy—and they said, ‘He’s not available.’ And I’m like, Whoa.” He said he was genuinely taken aback by the snub, despite the addled state Trump was obviously in at the time and the overall madhouse that the White House had become.

I asked Newsom if he had spoken with Trump since, or heard from him after the DeSantis donnybrook. He said no (a spokesperson for the former president echoed this), but my query appeared to trigger an odd reaction in Newsom. His face turned red, which I noted to him. “No, that’s because the sunlight is beaming on me,” he protested, pointing out the window into the expansive California glare.

Newsom said that my “line of questioning is interesting.” He offered a wordy zigzag of a reply: “The fact that you are not the first person to ask me ‘Did he call you?’—particularly some of your sophisticated colleagues—is suggestive.”

I found Newsom’s labyrinthine answer to also be “suggestive.”

Newsom has a personal connection to Trump, via his first wife, Guilfoyle. He does not love to discuss his ex. “I’m sensitive to the world I’m currently living in, at home particularly,” he told me. Still, he is asked about Guilfoyle a lot, mostly in the vein of “What’s the deal there?”

[From the October 2019 issue: The heir]

Newsom and Guilfoyle met in 1994, at a Democratic fundraiser in San Francisco. She worked in the district attorney’s office, and he owned a chain of local food and wine establishments. They married seven years later and were dubbed “The New Kennedys” in a Harper’s Bazaar spread. “Do I think he could be president of the United States?” Guilfoyle told the magazine. “Absolutely. I’d gladly vote for him.” That comment appears no longer operative. (Guilfoyle declined to comment for this article.)

Newsom and Guilfoyle divorced in 2006. Things ended amicably, Newsom said: “No kids, respect, both sides.” Newsom told me he wished Guilfoyle well, and not “backhandedly.” He did not want to say anything negative about her, even though, he said, “She’s taken shots at me publicly.”

In fact, in an interview on CNN’s The Axe Files podcast last year, Newsom said Guilfoyle had been a “different person” when they were married. He told me she was committed to “social justice and social” values, and that she was a Republican, “but it was more traditional conservatism.”

“She fell prey, I think, to the culture at Fox,” he said on the podcast. He added, “She would disagree with that assessment.”

Yes, she did.

“I didn’t change; he did,” Guilfoyle fired back in an interview with the right-wing commentator Charlie Kirk. She said Newsom was once a champion of entrepreneurs and small business but has since become “unrecognizable” to her. “He’s fallen prey to the left, the radical left.”

If Trump wins in November, Newsom will remain the governor of the nation’s most populous state and biggest resistance zone. In his office, he keeps a marked-up copy of a policy blueprint, “Project 2025,” prepared by the Heritage Foundation as a possible preview of a next Trump term. “I’m going through 100 pages of this. I’m not screwing around,” Newsom told me. He said his team is “Trump-proofing California,” preparing to enact whatever measures they can to thwart a hostile Republican White House. To better understand his political opposition, Newsom begins each morning with a heavy intake of far-right media. “There’s so many things that come our way that are so batshit-crazy,” he said. “You can’t deny where half of America lives.”

Newsom has endured a difficult few months in California. His approval ratings recently dropped under 50 percent for the first time since he became governor. He devoted a great deal of time and capital to promoting a ballot measure—Proposition 1—to allocate $6.4 billion to mental-health treatment programs. The proposal was expected to pass easily in March but barely did—a possible sign of weakness as Newsom faces another recall effort and a budget crisis.

After 90 minutes of conversation in his office, Newsom was getting antsy, as he does. He rose from the couch and walked over to his massive desk, where he would soon devour his daily helping of the California state fruit, over chicken salad.

Newsom is a student of workspaces. “I always like going in people’s offices, going, ‘Why is that there?’” he told me. He loved his usual quarters across the street, now deep in renovation. His desk there used to belong to Earl Warren, the former chief justice of the Supreme Court and the governor of California from 1943 to 1953. But Newsom assured me that no serious thought went into decorating these temporary quarters. He seemed pleased to give the impression of being a short-timer. “This is literally the things that came out of the first boxes,” he said. “We threw it up; a lot of it’s no rhyme or reason.”

One of Newsom’s prized mementos is a framed letter he received during the height of the COVID crisis, from none other than the baseball legend Willie Mays. “I don’t write many letters, but I’ve been watching you on TV and thought you might appreciate some words of encouragement,” the “Say Hey Kid” wrote.

[From the July/August 2023 issue: Moneyball broke baseball]

Newsom can be deeply cynical at times when discussing politics. But he can also display a boyish and even starstruck side. I watched him stare wide-eyed at his note from Mays and marvel. “Piles of ‘Go fuck yourself,’” Newsom said, describing his typical mail. “And then Willie Mays sends a letter.”

He showed me a few items in a side office, at the moment dominated by the big-screened head of the legal commentator Jonathan Turley yammering on Fox. A few feet away stood a picture of Newsom and Pelosi from the 1990s, in his first race for the San Francisco Board of Supervisors; shots of Schwarzenegger, Newsom’s late father, and various Kennedys; and a small table full of booze. Newsom hoisted a bottle of wine someone had recently given him: DeSantis, the vintage is called. I imagined a libation of complex and astringent notes, not at all supple or aromatic.

“I may send it to him,” Newsom told me. He said he wanted to strike up at least some tiny bit of rapport with the Florida governor during their Hannity encounter. “I tried, during every commercial break,” Newsom said. “We did the makeup.” Nothing. Newsom shook his head and imitated DeSantis, looking at his shoes, hands shoved into his pockets.

“Impossible,” he said. “Complete asshole.” (A DeSantis spokesperson declined to comment.)

Newsom said his distaste for DeSantis stems from what he describes as his Florida counterpart’s attacks on vulnerable targets—migrants, transgender and disabled people, often kids. Newsom himself was bullied as a child. He struggled with dyslexia, had a bowl haircut, and walked around school with a briefcase. The neighborhood kids could be merciless. He grew into a star athlete, 6-foot-3 with a potential run for president in his future. “But I’m still that kid,” he told me.

Being around Newsom, you sense an ongoing tug between boyish and sober impulses. He can fall heavily on nostalgia—and RFK quotes—while asserting himself as an agent of the future. He reveres the old-school pols who mentored him while striving to be inventive and distinct. It is vital, Newsom told me, “to take risks and not be reckless, but keep trying things.” To be original but restrained when necessary. “I don’t want to be derivative” might be as close as he comes to codifying a leadership philosophy: the Roger Bannister theory of life tempered by the venerated principle of waiting one’s turn, if it ever comes.

.png)

7 months ago

4

7 months ago

4

English (US)

English (US)