ARTICLE AD BOX

Photographs by Roger Kisby

The outcome of the presidential campaign, Republicans believed, was a fait accompli. “Donald Trump was well on his way to a 320-electoral-vote win,” Chris LaCivita told me this past Sunday as Democrats questioned, ever more frantically, whether President Joe Biden should remain the party’s nominee in November. “That’s pre-debate.”

LaCivita paused to repeat himself: “Pre-debate.”

This could be interpreted as trash talk coming from a cocky campaign: If you thought Biden was in trouble before he bombed at the June 27 debate, imagine the trouble he’s in now. But I heard something different in LaCivita’s voice.

One of the two principals tasked with returning Trump to the White House, LaCivita had long conceived of the 2024 race as a contest that would be “extraordinarily visual”—namely, a contrast of strength versus weakness. Trump, whatever his countless liabilities as a candidate, would be cast as the dauntless and forceful alpha, while Biden would be painted as the pitiable old heel, less a bad guy than the butt of a very bad joke, America’s lovable but lethargic uncle who needed, at long last, to be put to bed.

As the likelihood of a Trump-versus-Biden rematch set in, the public responded to the two candidates precisely as LaCivita and his campaign co-manager, Susie Wiles, had hoped. The percentage of voters who felt that Biden, at 81, was too old for another term rose throughout 2023, even as the electorate’s concerns about Trump’s age, 78, remained relatively static. By the end of the primaries, the public’s attitude toward the two nominees had begun to harden: One was a liar, a scoundrel, and a crook—but the other one, the old one, was unfit to be president.

In the months that followed, Trump and his campaign would seize on Biden’s every stumble, his every blank stare to reinforce that observation, seeking to portray the incumbent as “stuttering, stammering, walking around, feeling his way like a blind man,” as LaCivita put it to me. That was the plan. And it worked. Watching Biden’s slide in the polls, and sitting on hundreds of millions of dollars for an advertising blitz that would punctuate the president’s visible decrepitude, Trump’s team entered the summer believing that a landslide awaited in the fall.

Only one thing could disrupt that plan: a change of candidates atop the Democratic ticket.

There was always a certain danger inherent to this assault on Biden’s faculties. If Wiles and LaCivita were too successful—if too many Democrats decided, too quickly, that Biden was no longer capable of defeating Trump, much less serving another four years thereafter—then they risked losing an ideal opponent against whom their every tactical maneuver had already been deliberated, poll-tested, and prepared. Campaigns are usually on guard against peaking too soon; in this case, the risk for Trump’s team was Biden bottoming out too early.

In my conversations with LaCivita and Wiles over the past six months, they assured me multiple times that the campaign was planning for all contingencies, that they took quite seriously the possibility of a substitution and would be ready if Biden forfeited the nomination.

By mid-June, however, not long before the debate, their tone had changed. Trump was speaking at a Turning Point USA rally in Detroit and the three of us stood backstage, leaning against the wall of a dimly lit cargo bay, a pair of Secret Service vehicles idling nearby. When I asked about the prospect of Trump facing a different Democratic opponent in the fall, LaCivita and Wiles shook their heads. They told me it was too late; the most influential players in Democratic politics had become too invested in the narrative that Biden was fully competent and capable of serving another four years.

“We’re talking about an admission that the Democratic Party establishment would have to make,” LaCivita said. “We’re talking about pulling the plug—”

“On the president of the United States,” Wiles interrupted.

LaCivita nodded. “Who they’ve been saying up to this point in time is perfectly fine.”

No, Wiles and LaCivita agreed, the general-election matchup was set—and they were just fine with that.

“Joe Biden,” Wiles told me, allowing the slightest of smiles, “is a gift.”

But now, as we talked after the debate, it was apparent that they might have miscalculated. Elected Democrats were calling for Biden’s removal from the ticket. When I asked who Trump’s opponent was going to be come November, his two deputies sounded flummoxed.

“I don’t know. I don’t know,” Wiles said.

“Based off of the available public data,” LaCivita added, “he doesn’t look like he’s going anywhere.”

[Ronald Brownstein: The Biden-replacement operation]

Biden quitting the race would necessitate a dramatic reset—not just for the Democratic Party, but for Trump’s campaign. Wiles and LaCivita told me that any Democratic replacement would inherit the president’s deficiencies; that whether it’s Vice President Kamala Harris or California Governor Gavin Newsom or anyone else, Trump’s blueprint for victory would remain essentially unchanged. But they know that’s not true. They know their campaign has been engineered in every way—from the voters they target to the viral memes they create—to defeat Biden. And privately, they are all but praying that he remains their opponent.

I was struck by the irony. The two people who had done so much to eliminate the havoc and guesswork that defined Trump’s previous two campaigns for the presidency could now do little but hope that their opponent got his act together.

A crowd of Trump supporters in Phoenix (Roger Kisby / Redux for The Atlantic)

A crowd of Trump supporters in Phoenix (Roger Kisby / Redux for The Atlantic)

Wiles and LaCivita are two of America’s most feared political operatives. She is the person most responsible for Florida—not long ago the nation’s premier electoral prize—falling off the battleground map, having spearheaded campaigns that so dramatically improved the Republican Party’s performance among nonwhite voters that Democrats are now surrendering the state. He is the strategist and ad maker best known for destroying John Kerry’s presidential hopes in 2004, masterminding the “Swift Boat” attacks that sank the Democratic nominee. Together, as the architects of Trump’s campaign, they represent a threat unlike anything Democrats encountered during the 2016 or 2020 elections.

On the evening of March 5—Super Tuesday—I sat down with them in the tea room at Mar-a-Lago, an opulent space where intricate winged cherubs are carved into 10-foot marble archways. As the sun set behind the lagoon that borders the western edge of Trump’s property, the lights were also going out on his primary challengers. Soon the polls would close and the former president would romp across more than a dozen states, winning 94 percent of the available delegates and effectively clinching the GOP nomination. Trump had just one target remaining.

For an hour and 15 minutes, Wiles and LaCivita presented their vision for retaking the White House. They detailed a new approach to targeting and turning out voters, one that departs dramatically from recent Republican presidential campaigns, suggesting that suburban women might be less a priority than young men of color. They justified their plans for a smaller, nimbler organization than Biden’s reelection behemoth by pointing to a shrunken electoral map of just seven swing states that, by June, they had narrowed to four. And they alleged that the Republican National Committee—which, in the days that followed our interview, would come entirely under Trump’s control—had lost their candidate the last election by relying on faulty data and botching its field program.

In political circles, it’s considered a marvel that Trump won the presidency once, and came within 42,918 votes of winning it a second time, without ever assembling a sophisticated operation. Trump’s loyalists in particular have spent the past few years haunted by a counterfactual: Had the president run a reelection campaign that was even slightly more effective—a campaign that didn’t go broke that fall; a campaign that didn’t employ unskilled interlopers in crucial positions; a campaign that didn’t discourage his supporters from casting votes by mail—wouldn’t he have won a second term comfortably?

Wiles and LaCivita believe the answer is yes. Both have imported their own loyalists, making the campaign a Brady Bunch configuration led by the oddest of couples. Wiles, who runs the day-to-day operation, is small and self-possessed, a gray-haired grandmother known never to utter a profane word; LaCivita, a Marine combat veteran who charts the macro strategy, is a big and brash presence, famous for profane outbursts that leave Wiles rolling her eyes. They disagree often—staffers joke about feeling like the children of quarreling parents—but Wiles, who hired LaCivita, pulls rank. What unites them, with each other and Trump, is an obsession with winning. To that end, Wiles and LaCivita have never been focused on beating Biden at the margins; rather, their plan has been to bully him, to humiliate him, optimizing Trump’s campaign to unleash such a debilitating assault on the president’s age and faculties that he would be ruined before a single vote is cast this fall.

At one point that March evening, the three of us sat discussing the era of hyperpolarization that Trump ushered in. Given the trench-warfare realities—a vanishing center of the electorate, consecutive presidential races decided by fractions of percentage points, incessant governing impasses between the two parties—I suggested that Electoral College blowouts were a thing of the past.

They exchanged glances.

“You know, I could make a case—” Wiles began.

“I could too,” LaCivita said. He was grinning.

In the scenario they were imagining, not only would Trump take back the White House in an electoral wipeout—a Republican carrying the popular vote for just the second time in nine tries—but he would obliterate entire downballot garrisons of the Democratic Party, forcing the American left to fundamentally recalibrate its approach to immigration, economics, policing, and the many cultural positions that have antagonized the working class. Wiles and LaCivita wouldn’t simply be credited with electing a president; they would be remembered for running a campaign that altered the nation’s political DNA.

It’s a scenario that Democrats might have scoffed at a few months ago. Not anymore. “The numbers were daunting before the debate, and now there’s a real danger that they’re going to get worse,” David Axelrod, the chief strategist for Barack Obama’s two winning campaigns, told me in the first week of July. “If that’s the case—if we get to the point of fighting to hold on to Virginia and New Hampshire and Minnesota, meaning the main six or seven battlegrounds are gone—then yeah, we’re talking about a landslide, both in the Electoral College and in the popular vote.”

Axelrod added, “The magnitude of that defeat, I think, would be devastating to the party. Those margins at the top of the ticket would sweep Democrats out of office everywhere—House, Senate, governor, you name it. Considering the unthinkable latitude the Supreme Court has just given Trump, we could end up with a situation where he has dominant majorities in Congress and, really, unfettered control of the country. That’s not far-fetched.”

In the course of many hours of conversations with the people inside Trump’s campaign, I was struck by the arrogance that animated their approach to an election that most pundits long expected would be a third consecutive cliff-hanger. Yet I also detected a certain conflict, the sort of disquiet that accompanies abetting a man who is both a convicted felon claiming that the state is persecuting him and an aspiring strongman pledging to use the state against his own enemies. People close to Trump spoke regularly of his victimhood but also his own calls for retribution; they expressed solidarity with their boss while also questioning, in private moments, what working for him—what electing him—might portend.

At the center of the campaign, I would come to realize, is a comedy too dark even for Shakespeare: a mad king who shows flashes of reason, a pair of cunning viziers who cling to the hope that these flashes portend something more, and a terrible truth about what might ultimately be lost by winning.

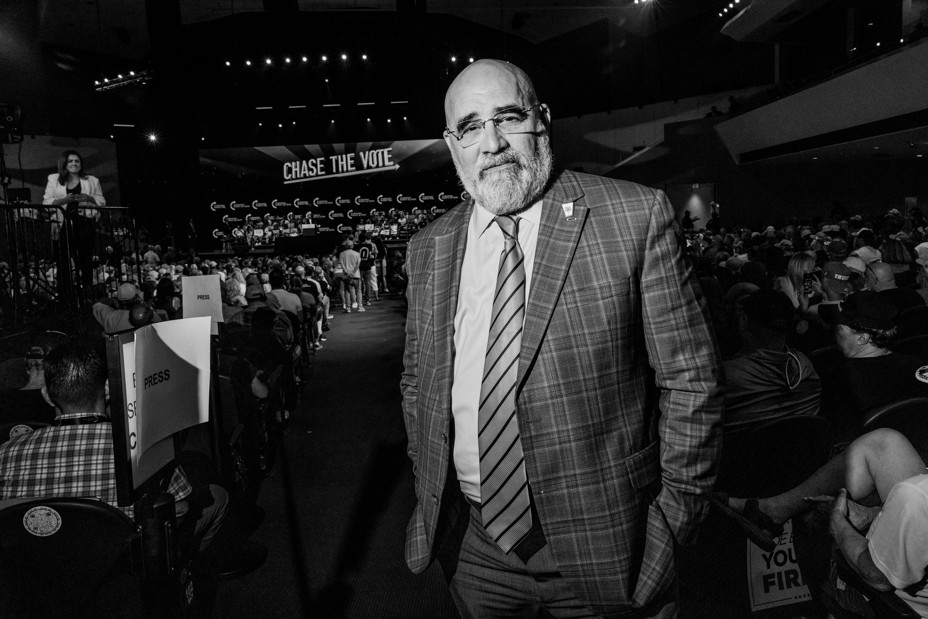

Chris LaCivita, who manages Trump’s 2024 presidential campaign with Susie Wiles (Roger Kisby / Redux for The Atlantic)

Chris LaCivita, who manages Trump’s 2024 presidential campaign with Susie Wiles (Roger Kisby / Redux for The Atlantic)

Long before Wiles took charge of Trump’s 2024 campaign, she appeared to be caught in a political love triangle. Having helped Ron DeSantis eke out victory in the Florida governor’s race of 2018—no small feat given the “blue wave” that crushed Republicans nationwide—Wiles was presumed to be charting his course as a presidential contender even as she kept ties with Trump, whose Florida campaign she ran in 2016.

But soon after DeSantis’s win, Wiles was suddenly and unceremoniously banished from the new governor’s inner circle. She swears she doesn’t know why. Maybe DeSantis couldn’t stand her getting the credit for his victory. Or perhaps he felt she was ultimately more loyal to Trump. Whatever the case, Wiles told me, working for DeSantis was the “biggest mistake” of her career—and she became determined to make him feel the same way about discarding her.

Her friends had been shocked when she’d agreed to work for Trump the first time around, and relieved when she joined DeSantis a couple of years later. Now, in late 2019, she was adrift—blackballed by the state’s political establishment, recently divorced, and fretting to friends about financial difficulties. (Wiles denied that part, saying, “I was able to pick myself up and get work without too much of a delay.”) She decided to rejoin Trump for the short term, agreeing to run his Florida operations in 2020, but what lay beyond was murky. All she knew, Wiles recalls thinking, is that she couldn’t be “nearly as trusting” going forward.

After Trump lost the 2020 election, Wiles faced a defining professional decision. Trump’s holdover political organization, a PAC called Save America, was fractured by infighting and needed new management. Wiles needed the work. But she knew the former president’s operation was a graveyard for political consultants. The only way she would say yes to Trump, she made it known, was if she took total control—answering to him and him alone. Trump agreed to that condition. Within days, the decree reached all corners of the Republican empire: There was a new underboss at Mar-a-Lago. Wiles, LaCivita told me, had established herself as “the real power behind the throne.”

They didn’t know each other back then; LaCivita had been affiliated with a pro-Trump outside group, but not with the candidate himself. He and Wiles had a mutual friend, though, in Trump’s pollster Tony Fabrizio. When Fabrizio arranged a dinner for the three of them in March 2022 at Casa D’Angelo, an Italian restaurant in Fort Lauderdale, LaCivita figured he was being buttered up to join Save America. But during that conversation, and over another dinner soon after, he realized Wiles wasn’t just looking for help with the PAC; Trump was planning to run again in 2024, and she needed a partner to help her guide his campaign. LaCivita was noncommittal. “You need to come meet the boss,” Wiles told him.

Sitting down with Trump for the first time, on the patio of Mar-a-Lago a few weeks later, LaCivita was overwhelmed. The music was blaring; Trump controlled the playlist from his iPad, sometimes ignoring the conversation at the table as he shuffled from Pavarotti to Axl Rose. Guests approached the table to greet the former president, repeatedly interrupting them. At times Trump seemed less interested in LaCivita’s qualifications than in his thoughts about a competitor, the Republican consultant Jeff Roe, who had sat in “that very chair” LaCivita occupied and shared his own theories about the 2024 election.

LaCivita would later tell me, on several occasions, that he’d had no misgivings about going to work for Trump. But according to several people close to him, that’s not true. These individuals, who spoke on the condition of anonymity to preserve their relationships with LaCivita, told me he’d been torn—appreciating the once-in-a-career opportunity before him while also recognizing that Trump was still every bit the erratic, combustible man who’d renounced his own vice president the moment he ceased to be completely servile. Wiles could sense LaCivita’s reluctance. When Trump decided later that year that he wanted to hire LaCivita, and requested his presence at his Bedminster club in New Jersey, she resorted to deception. “I knew if I said, ‘Chris, you’re going to come up here and the president’s going to put the hard sell on you and you’re going to get hired,’ he might not come,” Wiles told me. “So we tricked him.”

LaCivita went to Bedminster believing that Trump wanted to brainstorm ideas for television ads. Instead, two minutes into the conversation, Trump asked LaCivita: “When can you start?” LaCivita froze; he recalls nodding in the affirmative while struggling to articulate any words. “Susie, make a deal with him,” Trump said. “Let’s get this thing going.”

Almost immediately after he came on board in the fall of 2022, LaCivita’s new boss began to self-destruct. In late November, Trump hosted Ye (the rapper formerly known as Kanye West) and Nick Fuentes, a known anti-Semite and white supremacist, for dinner at Mar-a-Lago. Then, in early December, Trump proclaimed on social media that the supposedly fraudulent nature of Biden’s 2020 victory “allows for the termination of all rules, regulations, and articles, even those found in the Constitution.” Adding insult to self-inflicted injury, Trump blamed anti-abortion activists for the GOP’s poor performance in the midterm elections, infuriating an essential bloc of his political base.

“It was rough. Rough,” LaCivita told me.

In those early days, I wondered, did he regret saying yes to Trump?

“You know, I won’t go—” he stopped himself. “Look, on this level, a campaign is never without its personal and its professional struggles. That’s just the way it is.”

LaCivita wasn’t the only one struggling. When I started to ask Wiles to identify the low point of Trump’s campaign, she cut me off before the question was finished.

“Christmas. He was quiet over Christmas,” she said, alluding to the drubbing he took for the Ye-Fuentes dinner and his post about terminating the Constitution. That week, she told me, Trump asked Wiles a question: “Do you think I would win Florida?’”

He could feel his grip on the party loosening. Trump’s losing streak had coincided with DeSantis winning reelection by a million and a half votes in the fall of 2022. Already some major donors, operatives, and activists had defected to the Florida governor as he built a presidential campaign aimed at toppling Trump in the 2024 GOP primary.

“I said, ‘Yes, of course,’” Wiles recalled, biting her lip. “But I wasn’t sure.”

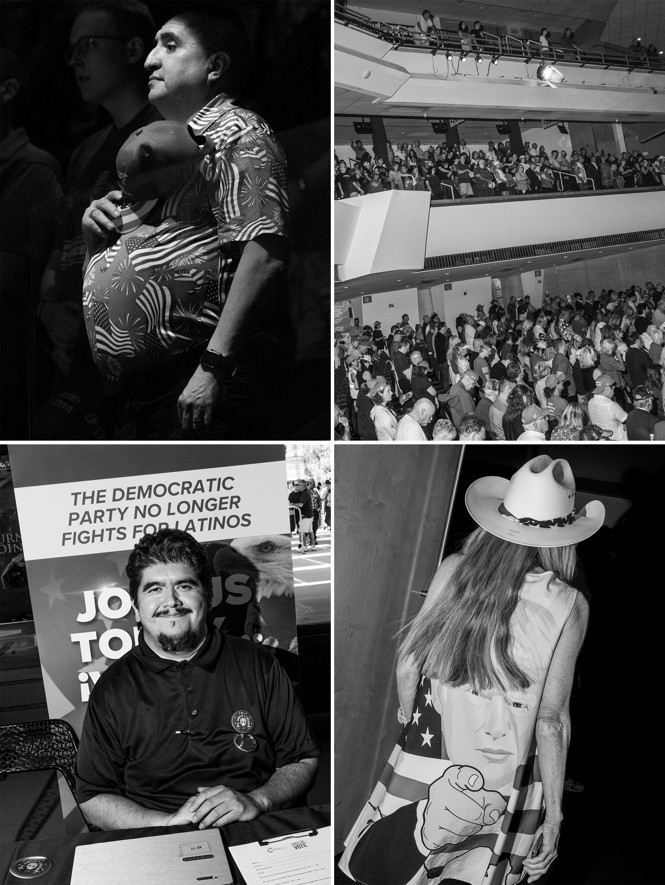

A representative from BLEXIT, a campaign to encourage Black Americans to leave the Democratic Party. For several years, polling has shown Black and Hispanic men drifting further right. (Roger Kisby / Redux for The Atlantic)

A representative from BLEXIT, a campaign to encourage Black Americans to leave the Democratic Party. For several years, polling has shown Black and Hispanic men drifting further right. (Roger Kisby / Redux for The Atlantic)

Wiles and LaCivita knew that DeSantis would stake his entire campaign on the Iowa caucuses. In 2016, Ted Cruz had defeated Trump there by building a sprawling ground game of volunteers and paid staffers who coordinated down to the precinct level. DeSantis was copying that blueprint, hiring Cruz’s senior advisers from that race while raising loads of money to construct an even bigger organization.

Trump had never gotten over being outmaneuvered by Cruz in Iowa. In fact, long before he declared America’s federal elections illegitimate, Trump had claimed that the 2016 caucuses were rigged. So when Wiles and LaCivita sat him down to discuss strategy in the state—warning him of what DeSantis had planned—Trump told them, matter-of-factly, “That can never happen again.”

Over the next year, two things became apparent. First, thanks to the constant suck of Trump’s legal fees on his political coffers—campaign insiders say that courtroom costs have accounted for at least 25 cents of every dollar raised by the campaign and affiliated PACs, an estimate that tracks with reporting elsewhere—Trump was not going to be able to spend money like DeSantis could in Iowa. Second, he might not need to.

In Florida, Wiles claims, she had discovered that there were roughly a million Trump supporters who had no history of engagement with the state party apparatus. And yet these people, when contacted by the GOP in 2016 and 2020, would sometimes become Trump’s most devoted volunteers. Wiles believed the same thing was possible in Iowa. So did LaCivita. This didn’t exactly represent a bet-the-house risk; Trump was always going to be favored against a big, fractured field, in Iowa and beyond. Still, Wiles and LaCivita saw in the opening act of the 2024 primary a chance to pressure-test a theory that could prove crucial later in the year.

Scouring precinct-level statistics from the four previous times Trump had competed in Iowa—the primary and general elections in 2016 and 2020—they isolated the most MAGA-friendly pockets of the state. Then, comparing data they’d collected from those areas against the state’s voter file, LaCivita and Wiles found what they were looking for: Some 8,000 of those Iowans they identified as pro-Trump—people who, over the previous seven or eight years, had engaged with Trump’s campaign either physically, digitally, or through the mail—were not even registered to vote. Thousands more who were registered to vote had never participated in a caucus. These were the people who, if converted from sympathizers to supporters, could power Trump’s organization.

Political consultants often consider eligible voters on a one-to-five scale: Ones being the people who never miss an election and hand out campaign literature in their spare time, fives being the reclusive types who can’t be canvassed, have never cast a vote, and probably never will. Most campaigns, especially in Iowa, focus their resources on the ones and twos. “There was this other bucket that we identified: low-propensity Trump supporters,” Wiles said. “We sort of took a gamble, but we were really sure that those tier-three people would be participating, that they would be our voters.”

Several times in the summer and fall of 2023, I heard from DeSantis allies who were bewildered by what Trump’s team was (and wasn’t) doing on the ground. “Our opponents were spending tens of millions of dollars paying for voter contacts for people to knock on doors,” LaCivita said. “And we were spending tens of thousands printing training brochures and pretty hats with golden embroidery on them.”

The gold-embroidered hats were reserved for “captains,” the volunteers responsible for organizing Trump supporters in their precincts. Notably, Wiles said, most of these captains came from the third tier of Iowa’s electorate—they were identified, recruited, and then trained in one of the hundreds of caucus-education sessions Trump’s team held around the state. At that point, the captains were given a list of 10 targets in their community who fit a similar profile, and told to turn them out for the caucuses. It was called the “10 for Trump” program. The best way to find and mobilize more low-propensity Trump supporters, the thinking went, was to deputize people just like them.

It appeared to work. On caucus night, as the wind chill plunged to 40 degrees below zero in parts of Iowa—and voter turnout plunged too—Trump won 51 percent of the vote, breaking an Iowa record, and clobbered DeSantis despite being heavily outspent. According to LaCivita, the precincts where the campaign invested heavily in the “10 for Trump” program saw a significant jump in turnout compared with the rest of the state.

That’s the story Wiles and LaCivita are telling about Iowa, anyway. Not everyone believes it. Trump enjoyed a sizable lead in the Iowa polls from the start, thanks in part to his allies blanketing the state with TV ads before his opponents were even out of the gate. Several people who worked on competing campaigns in Iowa said it was Trump’s first indictment, in March 2023—not his campaign’s ground game or anything else—that made him unbeatable. “When the Democrats started using the law to go after Trump, it hardened all of his very conservative supporters, some of whom had softened after 2022,” Sam Cooper, who served as political director for DeSantis, told me. “It was a race the Trump campaign locked up well before caucus day.”

The consensus of the political class post-2020 held that Trump’s base was maxed out; that any MAGA sympathizers who’d gone undiscovered in 2016 had, by the time of his reelection bid, been identified and incorporated into the GOP turnout machine. Wiles and LaCivita disagreed. They built a primary campaign on the premise that an untapped market for Trumpism still existed. But they knew that the true test of their theory was never going to come in Iowa.

Attendees at the Turning Point event in Phoenix. (Roger Kisby / Redux for The Atlantic)

Attendees at the Turning Point event in Phoenix. (Roger Kisby / Redux for The Atlantic)

Six miles inland from Mar-a-Lago, tucked inside a contemporary 15-floor office building that overlooks a Home Depot parking lot, is a presidential-campaign headquarters so small and austere that nobody seems to realize it’s there. When I told the security guard at the front desk that I’d come to visit “the Trump offices,” she gave me a quizzical look; only later, after hanging around for several hours, was I clued in to the joke that nobody in this building—not any of the dozen law firms, or the rare-coin dealer, or apparently even the security guard—has any idea exactly who occupies the second and sixth floors.

In fairness, Trump’s team used to inhabit just one of those floors. It was only after the merger with the Republican National Committee in early March, which eliminated dozens of supposedly duplicative jobs and relocated most of the RNC staff to Palm Beach, that additional space became necessary. Still, that a former president whose 2020 headquarters was something out of a Silicon Valley infomercial—all touch-screen entryways and floor-to-ceiling glass offices with dazzling views of the Potomac—was housing his 2024 operation in a plebeian office park signaled a sort of inverse ostentation, saying much about the personalities and priorities behind this campaign.

From day one, people familiar with internal deliberations told me, Wiles and LaCivita emphasized efficiency. There would be none of the excesses that became a staple of Trump’s 2020 reelection effort, which raised more than $1 billion yet unfathomably ran short of cash in the home stretch of the election. They needed to control all the money. And for that, they needed to control the national party apparatus.

[David A. Graham: Trump’s campaign has lost whatever substance it once had]

The Trump campaign’s takeover of the RNC in March—installing the former president’s daughter-in-law, Lara Trump, as the new co-chair, while establishing LaCivita as chief of staff and de facto chief executive, all of it long before Trump had technically secured the party’s nomination—didn’t sit well with many Republicans. Appearances aside, the imperatives of a presidential campaign are not always aligned with those of the RNC, whose job it is to advance the party’s interests up and down the ballot and across the country. “Party politics is a team sport. It’s bigger than Ronald Reagan or Donald Trump or any one candidate,” said Henry Barbour, a longtime Mississippi committeeman, who has fought to prevent the national party’s funds from going to Trump’s legal defense. “Nobody’s ever going to agree on exactly how you split the money up, but you’ve got to take a holistic approach in thinking about all the campaigns, not just one.”

The RNC under Ronna McDaniel, who chaired the national party from early 2017 until LaCivita’s takeover, had become a frequent target of Trump’s ire. He didn’t like that the party remained neutral in the early stages of the 2024 primary—and he was especially furious that McDaniel commissioned debates among the candidates. But what might have bothered him most was the RNC’s priorities: McDaniel was continuing to pour money into field operations, stressing the need for a massive get-out-the-vote program, but showed little interest in his pet issue of “election integrity.”

“Tell you what,” Trump said to Wiles and LaCivita. “I’ll turn out the vote. You spend that money protecting it.”

The marching orders were clear: Trump’s lieutenants were to dismantle much of the RNC’s existing ground game and divert resources to a colossal new election-integrity program—a legion of lawyers on retainer, hundreds of training seminars for poll monitors nationwide, a goal of 100,000 volunteers organized and assigned to stand watch outside voting precincts, tabulation centers, and even individual drop boxes.

To sell party officials on this dramatic tactical shift, Wiles and LaCivita pointed to the inefficiencies of the old RNC approach—of which there were plenty—and argued that they could run a more effective ground game with fewer resources. “The RNC has always operated on number of calls, number of door knocks, and nobody paid any attention to what the result of each of those was. We have no use for that,” Wiles told me. “It doesn’t matter to me how many calls you’ve made. What matters to me is the number of calls you’ve made and gotten a positive response from a voter … They considered success volume. It’s not.”

Several RNC insiders told me they agreed, at least broadly, with this critique. Yet they also said Trump’s team had grossly exaggerated the party’s past expenditures to serve the campaign’s mission of reallocating resources toward Trump’s election-integrity obsession. For example, LaCivita told me that, based on his review of the party’s 2020 performance, the RNC spent more than $140 million but made just 17.5 million voter-contact attempts. When I challenged that number, he conceded that it might have been closer to 27 million. But according to an internal RNC database I obtained, the party knocked on nearly 32 million doors in competitive states alone, and made another 113 million phone calls, for a total of some 145 million voter-contact attempts.

A wide array of party officials I spoke with said that McDaniel, who declined to comment for this story, had lost the confidence of her members. And none of them disputed that the RNC ground game needed reassessing. But the abrupt directional change announced by Wiles and LaCivita, these officials told me, could only be interpreted as financial triage. It was unfortunate enough that Trump’s legal-defense fund steadily drained the campaign coffers; his insistence on this sweeping, ego-stroking program to “protect the vote” was going to cost an untold fortune. Given these constraints, Wiles and LaCivita knew that they couldn’t run a traditional Republican field program.

Which is how I got to talking with James Blair.

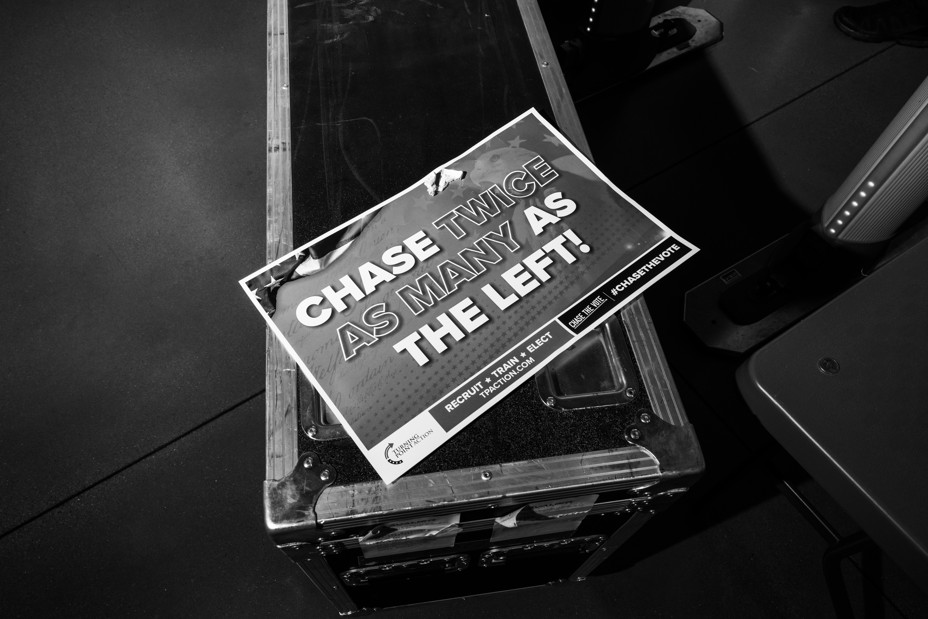

To thousands of cheering supporters, Trump declared that the 2024 election would be “too big to rig.” (Roger Kisby / Redux for The Atlantic)

To thousands of cheering supporters, Trump declared that the 2024 election would be “too big to rig.” (Roger Kisby / Redux for The Atlantic)

“In private equity, or investment in general, you look for highest upside at smallest input,” Blair, the 35-year-old political director for Trump and the RNC, told me, trying to justify their cut-rate ground game. “In a very basic sense, you can try to do everything all the time—and often the result is you do nothing particularly well—or you can try to do a few things that deliver high value compared to their relative input level.”

We were sitting in a sterile second-floor conference room, the whiteboard to my left freshly wiped down, at the campaign’s headquarters. The space outside was more colorful, with depictions of the 45th president adorning the walls: an elaborate In Trump We Trust mural; a blown-up birthday poster, signed by some of his spiritual advisers, depicting Trump under the watch of a lamb, a lion, a white horse, and two doves; a framed replica of Trump’s mug shot, in the style of the Obama-era HOPE poster, above the words NEVER SURRENDER. On a stretch of wall outside the conference room, large black letters spelled out the campaign’s mantra: Joe Biden is: Weak, Failed and Dishonest.

Blair wore the expression of a man who knows something the rest of us don’t. He studied finance at Florida State, then accepted an entry-level job at the statehouse in Tallahassee, with plans to eventually pivot toward a career in business. Instead, he ended up running legislative races for the state GOP in 2016, overseeing the DeSantis campaign’s voter-contact program in 2018, and then joining the new governor’s office as deputy chief of staff. As with many Wiles loyalists, Blair’s time in DeSantis’s orbit was brief, and his reunion with Wiles in Trumpworld—her allies on the campaign are known as “the Florida mafia”—was inevitable.

Blair, like Wiles, believes that campaigns have become beholden to empty statistics. “If you chase numbers in terms of top-line output, you make tactical decisions that increase that goal,” he said. “So that would be dense suburban areas where you can hit more doors per hour, right? More doors per body [equals] higher output.” The problem, Blair said, is that most of those doors aren’t worth knocking on: Turnout is already highest in the suburbs, and fewer and fewer voters there remain truly persuadable, for reasons of hardened partisan identification along economic or cultural lines. And yet, since the days of Karl Rove, campaigns have blanketed the country with paid canvassers, investing hundreds of millions of dollars in contacting people who are already going to vote and who, in most cases, already know whom they’re voting for.

This is the crux of Team Trump’s argument: Now that the electoral landscape looks so different—both campaigns fighting over just a handful of states, a finite number of true swing voters in each—shouldn’t the party reassess its strategy? Especially given the campaign’s financial burdens, some Republicans agree that the answer is yes. One of them is Rove himself.

“There are two groups of people to consider: the low-propensity Republicans and the persuadable swing [voters]. Be careful that you’re not antagonizing one with your outreach to the other. You don’t want people knocking on the swing doors wearing ‘Let’s Go Brandon’ shirts,” Rove told me. When it comes to running a ground game in this environment, he added, “the priority should be maximizing turnout among the true believers,” who, if they vote, are a lock for Trump.

This isn’t to say Trump’s campaign won’t be targeting those persuadable voters. It’s just a matter of preferred medium: If Wiles has to drop millions of dollars to engage the suburban mom outside Milwaukee, she’d rather that mom spend 30 seconds with one of LaCivita’s TV spots than 30 seconds with a pamphlet-carrying college student on her front porch. This is the essence of Trump’s voter-contact strategy: pursuing identified swing voters—college-educated women, working-class Latinos, urban Black men under 40—with micro-targeted media, while earmarking ground resources primarily for reaching those secluded, MAGA-sympathetic voters who have proved difficult to engage.

[Stephanie McCrummen: Biden has a bigger problem than the debate]

The campaign, I was told, hopes to recruit somewhere between 5,000 and 10,000 captains in each of the seven battleground states: Arizona, Georgia, Michigan, Nevada, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin. They won’t all be low-propensity Trump supporters, as they were in Iowa—there isn’t time to be that selective—but they will be trained in the same way. Each will be assigned a roster of people in their communities, 10 to 50 in total, who fit the profile of Trump-friendly and electorally disengaged. “Our in-house program is focused on doing the hardest-to-do but highest-impact thing,” Blair said, which is contacting the MAGA-inclined voters whom previous Trump campaigns missed.

In truth, “hardest-to-do” might be an understatement. Blair was describing this program to me in early June; building it out by the time early voting begins in September is akin to a three-month moonshot. (He declined to share benchmarks demonstrating progress.) Republican officials in key states, meanwhile, have complained for months about the Trump campaign’s practically nonexistent presence on the ground. When they’ve been told of the plan to scale back traditional canvassing operations in favor of a narrower approach, their frustration has at times turned to fury.

“The RNC had promised us a lot of resources, but there’s been a huge pullback. And the Trump team isn’t standing up its own operation, so we’re really behind,” Jason Cabel Roe, a GOP consultant in Michigan who’s handling the state’s most competitive congressional race, told me. “The state party’s a mess; they’re not going to pick up the slack. When I talk to other Republicans here, they say the same thing: ‘Where are the resources for a field operation?’”

Trump officials acknowledge that these concerns are legitimate. Democrats have opened hundreds of field offices and positioned more than 1,000 paid staffers across the battleground map, while the Trump team is running most of its presidential operations out of existing county-party offices and employing fewer than a dozen paid staffers in most states. The great equalizer, they believe, is intensity: Whereas Democrats have struggled to stoke their base—multiple swing-state Biden allies told me that volunteer recruiting has been anemic—Republicans have reported having more helpers than they know what to do with. In this context, Trump’s enlisting unpaid yet highly motivated voters to work their own neighborhoods, while the Democrats largely rely on parachuting paid staffers into various locations, might not be the mismatch Republicans fear.

The Trump campaign’s approach wouldn’t be feasible in most presidential elections. But in 2024, LaCivita told me, there are “probably four” true battlegrounds: Arizona, Michigan, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin. (He said the campaign feels confident, based on public and private polling, as well as its own internal modeling, that Georgia, Nevada, and North Carolina are moving out of reach for Biden.) In this scenario, Trump’s team doesn’t need to execute a national campaign. They are “basically running four or five Senate races,” Beth Myers, a senior adviser to Mitt Romney’s 2012 campaign against Barack Obama, told me. “And they can get away with it, because the playing field is just that small now.”

Myers is no Trump fan. Still, she credits Wiles and LaCivita with developing a strategy that recognizes both the “excesses” of past Republican campaigns and the realities of a new electorate. In 2012, Romney and Obama fought over a much larger map that included Florida, Ohio, Iowa, Virginia, Colorado, New Hampshire, and even, at least initially, Missouri and Indiana. “Vendors got involved and started telling us that we needed seven ‘touches’—that the number of contacts was more important than who we were contacting,” Myers said. “But we got that wrong. I think the quality of the touch is much more important than the quantity of the touch, and I think that’s what Chris is doing here.”

Notably, thanks to a new Federal Election Commission opinion that allows campaigns to coordinate canvassing efforts with outside groups, there will still be an enormous field operation working on Trump’s behalf. Blair explained that allied organizations such as Turning Point Action, America First Works, and the Faith and Freedom Coalition would handle much of the right’s canvassing effort moving forward, focusing on the “standardized volume plays” as the campaign itself takes a specialized approach. (This isn’t the relief Republicans officials have been hoping for: Turning Point, for example, became a punch line among GOP strategists and donors after it promised to deliver Arizona— where its founder, Charlie Kirk, resides—in the 2022 midterms, only for Democrats to win every major statewide race. Kirk’s group is assuring dubious party officials and major donors that its operation has scaled up, but several told me they aren’t buying it.)

Blair knows the campaign can’t ignore the outcry from local Republicans. As we ended our conversation, he was heading to his office to lead a conference call with county chairs in battleground states, part of an effort to “educate” them about the program and “get buy-in.”

If one thing has calmed Republican nerves, it’s the recent, record-breaking fundraising haul that accompanied Trump’s conviction in the New York hush-money case. A campaign that was once being badly outraised brought in more than $70 million in the 48 hours after the verdict. Suddenly—and to the shock of both campaigns—Trump entered July with more cash on hand than Biden.

But this windfall hasn’t altered the plans of Wiles and LaCivita. Even when the money was pouring in, it was too late, they told me; the campaign’s tactical decisions for getting out the vote had already been made. Around this same time, I noticed that it wasn’t just those swing-state Republicans getting anxious. The day before I visited headquarters, one Trump aide, who requested anonymity to speak candidly, confessed to me that doubts about the field strategy permeate this campaign. This person predicted that Wiles, LaCivita, and Blair will either look like geniuses who revolutionized Republican politics—or the biggest morons ever put in charge of a presidential campaign.

“I accept that framing,” Blair told me, flashing a smirk. “And I live by it every day.”

As Blair and I stood up to leave the conference room, he stopped me. The smirk was gone. He wanted to make something clear: He takes these decisions very seriously. “Because if we lose,” he said, “I think there’s a pretty good chance they’re going to throw us in jail.”

It was a startling moment. I’d heard campaign aides make offhand remarks before about expecting to end up incarcerated for helping Trump. But this was more direct, more paranoid. Blair was telling me that, in a second Biden administration, he expected deep-state flunkies to arrest him for the crime of opposing the president. And he wasn’t alone. Brian Hughes, a campaign spokesperson known for his extensive government work and generally affable demeanor, nodded in agreement as Blair spoke. “I think we all feel that way,” Hughes said.

A sign for Turning Point’s “Chase the Vote” initiative, a door-knocking effort aimed at encouraging mail-in voting. In Arizona, Wiles and LaCivita have outsourced much of the Trump campaign’s canvassing operations to Turning Point. (Roger Kisby / Redux for The Atlantic)

A sign for Turning Point’s “Chase the Vote” initiative, a door-knocking effort aimed at encouraging mail-in voting. In Arizona, Wiles and LaCivita have outsourced much of the Trump campaign’s canvassing operations to Turning Point. (Roger Kisby / Redux for The Atlantic)

Throughout our conversations, Wiles and LaCivita kept insisting to me that something important has changed about Donald Trump. As they tell it, the man who once loathed making donor calls is now dialing for dollars at seven in the morning, unprompted. The man who could never be bothered with the fine print of Iowa’s caucuses finally sat down and learned the rules—and then started explaining them to Iowans at his pre-caucus events. The man who treated 2016 like a reality show and 2020 like a spin-off now speaks of little else but winning.

This may all be the stuff of reverential narratives. Yet there is no denying the consequence of Trump’s evolution on one tactical front: voting by mail. In 2020, the president railed against the practice, refusing to heed the advice of campaign aides who told him, given the shifting nature of consumer behaviors during the pandemic, that absentee votes would almost certainly decide the election. This time around, Wiles led a months-long effort to educate her boss on the practice, explaining how Republicans in Florida and elsewhere had built sprawling, successful operations targeting people who prefer not to vote in person. Wiles pressed Trump on the subject over the course of at least a dozen conversations, stretching from the pre-Iowa season all the way into the late springtime, pleading with him to bless the campaign’s effort to organize a voter-contact strategy built around absentee ballots.

“It wasn’t like we went in there one day and said, ‘Okay, today we’re gonna say we like mail-in ballots.’ It doesn’t happen that way,” Wiles told me at one point. “As he better understood campaign mechanics, he understood, you know, why this—”

“Winning!” LaCivita chimed in, palms raised, growing impatient with the explanation.

Wiles shot him a look. “Why this was important,” she said.

The funny thing, Wiles noted, is that she can’t take credit for convincing Trump. It was “a person who will remain nameless”—someone from outside the campaign, who happened to be kibitzing with the former president about his own reasons for voting by mail—who said something that jolted Trump’s brain. “That’s when the switch flipped. And that is very typical,” Wiles said, chuckling. “You work on something, work on something, work on something, and then in some bizarre, unexpected way, somebody phrases it differently—or it’s somebody that he particularly respects in a particular area who says it—and that’s it.”

The campaign is now engineering a mobilization program aimed at making absentee voting seamless and customizable based on each voter’s jurisdiction. (The initiative, dubbed “Swamp the Vote,” comes with face-saving disclaimers about this being necessary only to defeat the sinister, election-stealing left.) This project might not assuage the Trump-fueled fears of Republican base voters, but that’s hardly the point. His campaign sees the mail-voting push as a path to attracting a slice of the electorate that the Republican Party has spent two decades ignoring: low-propensity left-leaning voters, especially young men of color, who, due to some combination of panic and boredom, turned out for Biden in 2020.

These voters are one explanation as to how Democrats ran up an unthinkable 81-million-vote total in the last presidential election—and, more to the point, increased their margins in places such as Phoenix, Detroit, Milwaukee, and Philadelphia. For the past several years, however, polling has shown Black and Hispanic men drifting further right—a trend sharply accelerated by the Biden-Trump rematch. If the Republican nominee can siphon off any significant chunk of those voters in November—persuading them to mail in a ballot for him instead of sitting out the election—the math for the Democrats isn’t going to work. That could make November a realignment election, much like Obama’s win in 2008: one that shifts perceptions of voter coalitions and sends the losing side scrambling to recalibrate its approach.

Ironically enough, it was Obama’s dominant showings with nonwhite voters in 2008 and 2012—winning them by margins of four to one—that inspired a Republican autopsy report that called for kinder, gentler engagement with minority communities. Now record numbers of Black and Latino men might be won over by the same candidate who prescribes mass deportations, trafficks in openly racist rhetoric, and talks about these voters in ways that border on parody. “He says stuff like ‘The Blacks love me!’’” LaCivita remarked to me at one point. He threw his arms up, looking equal parts dumbfounded and delighted. “Who the fuck would say that?”

Wiles, for her part, wanted to be clear about the campaign’s aims. “It’s so targeted—we’re not fighting for Black people,” she said. “We’re fighting for Black men between 18 and 34.”

[Ronald Brownstein: How Trump is dividing minority voters]

When she told me this, we were standing together backstage—LaCivita, Wiles, and me—at the Turning Point USA event in Detroit. Most of the faces in the crowd were white; the same had been true a few hours earlier, when Trump spoke at a Black church on the city’s impoverished west side. But that didn’t matter much to Wiles and LaCivita. The voters they’re targeting wouldn’t even know Trump was in Detroit that day, much less come out to see him. These aren’t people whose neighborhoods will be canvassed by Republican volunteers; rather, they will be the subject of a sweeping media campaign aimed at fueling disillusionment with the Democratic Party.

As we stood chatting, I remembered something that one of Trump’s allies had told me months earlier—a sentiment that has since been popularized and described in different ways: “For every Karen we lose, we’re going to win a Jamal and an Enrique.” Wiles nodded in approval.

“That’s a fact. I believe it. And I so believe we’re realigning the party,” she told me.

Wiles paused. “And I don’t think we’re gonna lose all the Karens, either. They buy eggs. They buy gas. They know. They may not tell their neighbor, or their carpool line, but they know.”

Just to be clear, I asked: If the Trump campaign converts significant numbers of Black and Hispanic voters, and holds on to a sizable portion of suburban white women, aren’t we talking about a blowout in November?

“We are,” Wiles said.

This is the scenario Trump craves, the one he’s been talking about at all of his recent rallies: winning by margins that are “too big to rig.” I had to wonder, though: What if the campaign’s models are wrong? What if, yet again, the election is decided by thousands of votes across a few key states? Wiles and LaCivita had accommodated Trump’s request to spend lavishly on an “election integrity” effort. But had they accommodated themselves to his lies about the last election—and what might be required of them next?

One afternoon in early June, as we sat in the hallway of an Arizona megachurch—Trump was delivering some fire and brimstone inside the sanctuary, decrying the evils of illegal immigration and drawing chants of “Bullshit! Bullshit! Bullshit!”—I asked LaCivita if he felt additional pressure running this particular campaign: Winning meant Trump would avoid further criminal prosecution; losing could mean more convictions and even incarceration. Either way, I suggested, this would be Trump’s last campaign.

“I don’t know,” LaCivita said, a smile spreading across his face. “I read somewhere that he was gonna change the Constitution so he could run again!” He was soon doubled over, howling and smacking both palms on his knees. It was an odd scene. When he finally came up for air, LaCivita told me, “I’m being sarcastic, of course.” Another pause. “I’m joking. Of course I am!”

If he was really joking, I replied, there was no need to keep clarifying that it was a joke.

“No, no,” LaCivita said, straightening his tie. “I just get a kick out of it.”

LaCivita tries to laugh off stress whenever possible. The Trump campaign, he said, is a “360-degree shooting gallery” in which “everybody is coming after you, internally and externally,” all the time. On any given day, he might be cleaning up after a particular staffer who has gone rogue with reporters, or extinguishing rumors he says are being spread about him by Trump’s confidant Richard Grenell (“he just likes to cause trouble”), or refuting supposed policy plans for the second Trump administration being floated by “those quote-unquote allies” on the MAGA right. (“It’s the Project ’25 yokels from Heritage. They and AFPI”—the America First Policy Institute, another think tank—“have their own little groups that raise money. They grift, and they pitch policy,” LaCivita said. “They have their own goals and their own agendas, and they have nothing to do with winning an election.”) In his mind, all the “noise”—Trump’s authoritarian spitballing very much included—is a source of levity.

There was a time, however, when LaCivita didn’t find it so funny. According to several people close to him, he was alarmed by Trump’s rise in 2016. After he came to terms with Trumpism, as so many in the party eventually did, his qualms were rekindled by the January 6 insurrection. Then came the opportunity to help run the 2024 campaign. Once again, LaCivita hesitated. And once again, LaCivita gave in—only to find himself, a few weeks into the job, working for a man who was dining with a neo-Nazi and toying with the idea of terminating the Constitution. After a while, he became resigned to these feelings of dissonance, friends told me, and eventually desensitized to them altogether. His focus was winning: demolishing Biden, electing Trump, ushering in massive Republican legislative majorities. But had he given much thought to what that success might mean?

Not long after our conversation in Arizona, I met LaCivita for breakfast on Capitol Hill, near his office at the RNC. Later that day, his boss would meet with House and Senate Republicans—many of whom, like LaCivita, had been ready to throw Trump overboard a couple of years ago, and who now stood and saluted like the North Korean military. As we sipped coffee, I asked LaCivita about the potential “termination” of the Constitution that the former president floated in 2022.

“I don’t know if he used the word terminate,” LaCivita said, squinting his eyes. “I think he may have said change or something.” (Trump did, in fact, say termination.)

Certainly it’s plausible that a hired gun, someone who cares about winning and winning only, could have genuinely forgotten the language used by his employer. And yet, according to several people familiar with the fallout, LaCivita—a Purple Heart recipient who lost friends in the Gulf War—was so bothered by the social-media post that he confronted Trump about it himself.

LaCivita confirmed to me that he’d called Trump about the post. In his telling, Trump responded that people were twisting his words, then agreed to issue a statement declaring his love for the Constitution. And that was that, LaCivita said, offering a shrug. He likened it to football: When the quarterback throws an interception, the team has to move on. No dwelling on the last play.

As he shoveled over-hard eggs into his mouth, Marine Corps cufflinks were visible beneath his dark suit. LaCivita had sworn an oath to the Constitution; he’d risked his life for the Constitution. Didn’t a part of him, when he read that post, think about the implications beyond political strategy?

“I mean, he took an oath to the Constitution too, as president of the United States,” LaCivita said. “I never put myself in a position of judging somebody.”

LaCivita thought for a moment. He told me that he’d sat in the courtroom on the second day of Trump’s hush-money trial in May. “Listening to the stuff they’re saying, meant for no other reason than to harm the guy politically—it just pissed me off,” he said. “It made me that much more determined.”

Now we were getting somewhere. Do the people who enter Trump’s orbit, I asked, become hardened by the experience? Do they adopt his persecution complex? Do they take the insults to him personally?

“I don’t psychoanalyze myself, and I sure as hell don’t psychoanalyze the people that I work for,” LaCivita told me. “But I truly believe that the things that he can do as president can actually make the country a whole lot better. You don’t do this at this level for transactional purposes.”

No doubt LaCivita is conservative by nature: pro-gun, anti-abortion, viscerally opposed to Democratic orthodoxy on illegal immigration and gender identity. At the same time, he has worked for Republicans who span the party’s ideological spectrum—most of them moderates who, he admits, reflect his own “center right” beliefs.

Just recently, I told LaCivita, I’d read an interview he’d given to his hometown newspaper, The Richmond Times-Dispatch, more than a decade ago. One quote stood out. Reflecting on his appetite for the fray—as a Marine, as a hunter, as a political combatant—LaCivita told the interviewer: “A warrior without war is miserable.”

When I looked up from reading the quote, LaCivita was nodding.

“People hire me to beat Democrats,” he said. “That’s what I do. That’s what Chris LaCivita does. He beats Democrats, period.”

He paused. “And Donald Trump gave me the opportunity of a lifetime.”

That much is true. Political consultants spend their careers dreaming of the day they’re called upon to elect a president, and those who succeed gain a status that guarantees wealth and prestige. I couldn’t help but think of how Wiles, the seasoned strategist who’d been humiliated by Florida’s young hot-shot governor, had hitched her career to Trump during his post–January 6 political exile. “The last time he was in Washington,” she said, “he was being run out of there on an airplane where nobody came to say goodbye.” Now Trump was barging his way back into the White House—and those same Republicans who once accused him of treachery, she noted, were cheering him on.

“He didn’t change,” Wiles told me. “They changed.”

I wanted to know if Wiles had changed. She boasted to me, during one conversation, that she had been somewhat successful in getting her boss to cut back on the rigged-election talk on the campaign trail. (“People want to have hope, they want to be inspired, they want to look forward,” she said.) But in that same conversation, Wiles could not answer the question of whether the 2020 election had actually been stolen. “I’m not sure,” she said, repeating the phrase three times.

And her boss?

“He thinks he knows,” Wiles said.

She paused, seeming to catch herself. “But we know,” Wiles added, “that it can’t happen again.”

Her moment of hesitancy stood out. One of the maxims of this campaign, something LaCivita drills into his staff, is that self-doubt destroys. (“You’re either right or you’re wrong,” he said. But you can’t second-guess decisions “once the bullet leaves the chamber.”) Which, as we sat inside that diner on Capitol Hill, one block from the scene of the January 6 carnage, returned us to the question of Trump’s threat against the Constitution. If LaCivita were to acknowledge his trepidation about the man he’s working for—

“Boom!” he said, interrupting with a faux gunshot noise. “You’re done. You’re done. Hesitation in combat generally gets you killed.”

Even if you’re hesitating for good reason?

“Hesitation in combat gets you killed,” LaCivita said again, leaning across the table this time. He pounded his fist to punctuate every word: “I. Don’t. Hesitate.”

In that moment, the sum of my conversations with LaCivita and Wiles and their campaign deputies began to make sense. For all their lofty talk of transformation—transforming their boss’s candidacy, transforming Republican politics, transforming the electorate, transforming the country—it continues to be Trump who does the transforming.

.png)

4 months ago

4

4 months ago

4

English (US)

English (US)