ARTICLE AD BOX

Hair loss is common in men and women, particularly with age – for example, androgenetic alopecia (or pattern baldness) affects 80% of men and 40% of women. For the most part, it can be physically inconsequential.

Yet, modern society has a distaste for hair loss. Look at how news stories have speculated about whether ten-year-old Prince George and his younger brother, Louis, will inherit their father's “baldness genes”.

The market in hair restoration procedures is projected to be worth £10 billion by 2026. You can even purchase wigs for babies that proclaim to make children up to three years old “more attractive”.

It wasn't always this way. In many cultures and periods of history, baldness has been revered, from ancient Egypt to the 18th century people of Issini (modern-day Ghana). Shaved and bald heads could represent purity, a rejection of superficiality, and be ritualised through daily shaving.

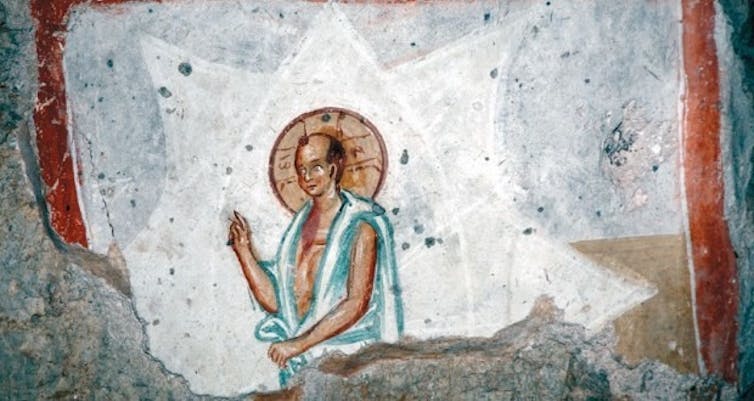

The fresco of a young, bald-headed Jesus in Cave Church of Sts. Peter and Paul, Serbia. непознати/Wikimedia Commons, CC BY

The fresco of a young, bald-headed Jesus in Cave Church of Sts. Peter and Paul, Serbia. непознати/Wikimedia Commons, CC BY

Bald heads have also been positively associated with divinity. Medieval and Christian art includes balding depictions of Jesus and Madonna. Today, Buddhist monks, nuns and other political and religious groups routinely shave their heads.

In the west in the 19th century, baldness also came to be celebrated. But rather than for religious reasons, it was for pseudoscientific ones that were tied in with harmful ideas about intelligence and race. It set a precedent for a Eurocentric bias in hair-loss research that continues to this day.

Eugenicists and hair loss

Ten years after Charles Darwin published his famous evolutionary thesis “On The Origin of Species” in 1859, his cousin Francis Galton extended it to suggest that some groups of humans were more evolved than others. Galton and others used any observable differences in humans, including variation in skin colour and hair, as “proof” of distinct human races, some of which were supposedly superior to others.

Black people in particular were pseudoscientifically classified as being differently haired and evolutionarily inferior to white people. Victorian eugenicists regarded black people's hair as animal fur, arguing they had been the same “blackskinned, woolly-headed animal[s] for the last 2,000 years”.

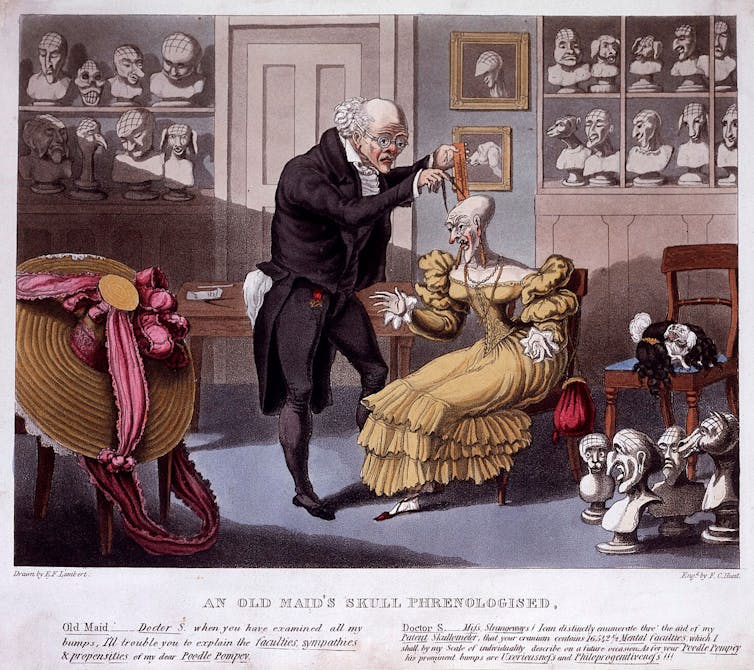

Related to eugenics was the pseudoscience of phrenology, which attempted to predict traits like personality and morality from physical characteristics. These included a person's head shape, complexion and head hair amount. Phrenology, which has been thoroughly discredited, was used to uphold scientific racism, the idea that race is biological and that some races are superior to others.

The Victorian writer Henry Frith wrote in his 1891 book, How to Read Character in Features, Forms and Faces: “The hairless men are the intellectual ones: their mental and bodily strength are both considerable … brain dominates matter in the bald”.

Such ideas were combined with the false belief in white men's superiority and intelligence compared to other “hairier” races. Frith wrote: “White and, comparatively, hairless races hav[e] dominion in the world [over the] strong, wild, hairy races.”

American medical students were taught “that slaves, Indians, women and donkeys never go bald because of their small and undeveloped brains”. In 1902, medical doctor David Walsh wrote a book on hair diseases in which he stated: “Baldness is practically unknown among savages.”

Shockingly, such eugenicist logic remained unchallenged until the late 20th century. In 1966, the dermatologist Ian Martin-Scott concluded: “In coloured races baldness is a rarity and virtually unknown in many semi-civilised communities”.

Phrenologists thought your skull shape determined your personality. Wellcome Collection

Phrenologists thought your skull shape determined your personality. Wellcome Collection

Diversity in hair loss matters

Today, such false beliefs are thankfully rare in science. However, as in many areas of medical research, studies and clinical trials into hair loss predominantly focus on white people, ignoring or excluding other racial groups.

Social psychologist Hannah Frith (no relation) and I recently reviewed psychology studies that collectively researched more than 10,000 balding men. We found almost all of the research participants were European or Asian, with just 1% from South America or Africa.

Meanwhile, dermatologists and other hair-loss practitioners continue to routinely study medical textbooks that only include images of white scalps and straight-textured hair.

This is a problem because, as recent (and limited) research shows, hair loss is common in all racial and ethnic groups. A 2022 study reviewed data from almost 200,000 UK men (aged 38-73). The researchers found 68% of white men reported hair loss compared to 64% of South Asian men and 59% of black men. (The relatively small differences are partially explained by the fact the white men in the study were older).

There are also forms of hair loss that are known to be more common in people of colour. For example, Asian women are more likely to have alopecia areata, an autoimmune condition that causes hair loss.

Black people are more likely to develop traction alopecia, a hair loss type related to constant pulling of the hair follicles including through tight hairstyles. This condition highlights the impact of a racist society on hair.

Specifically, black people may feel compelled to conceal their afro-textured hair (stereotyped as uncivilised) through weaves, braids and chemical relaxers. All of these practices can be physically damaging, including to the hair follicles.

Alopecia resources that are racially inclusive (by the Centre of Evidenced-based Dermatology) help dermatologists make more realistic recommendations that situate people's hair concerns within their societal and cultural contexts.

A better understanding of the racism of hair loss research is important. It reminds us that neither the texture, colour nor amount of hair a person has conveys anything meaningful about them, evolutionarily or otherwise.![]()

(Author: Glen Jankowski, Senior Lecturer in the School of Social Sciences, Leeds Beckett University)

(Disclosure Statement: Glen Jankowski does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment)

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

(This story has not been edited by NDTV staff and is auto-generated from a syndicated feed.)

.png)

8 months ago

2

8 months ago

2

English (US)

English (US)